MER Spirit

MER Opportunity

- Descent Images

- Crater Panorama

- Rover Arm - Stereo Image

- Soil Closeup

- Egress

- Bedrock Outcrop

- Descent Stage on Plain

- Stone Mountain

- Stone Mountain Layers

- Guadalupe Closeup

- Jarosite Spectrum

- Minerals formed in Water - PR

- Berry Bowl

- Berries Closeup

- Rock Outcrop Labelled

- Berries Contain Hematite - PR

Link to Source: NASA JPL Mars Rovers Site

Michael Gallagher

Opportunity Rover Finds Strong Evidence Meridiani Planum Was Wet

|

|

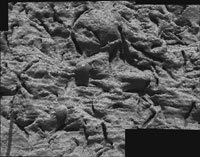

This image, taken by Opportunity's microscopic imager, shows a portion of the

rock outcrop at Meridiani Planum, Mars, dubbed "Guadalupe." |

Evidence the rover found in a rock outcrop led scientists to the conclusion. Clues from the rocks' composition, such as the presence of sulfates, and the rocks' physical appearance, such as niches where crystals grew, helped make the case for a watery history.

"Liquid water once flowed through these rocks. It changed their texture, and it changed their chemistry," said Dr. Steve Squyres of Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y., principal investigator for the science instruments on Opportunity and its twin, Spirit. "We've been able to read the tell-tale clues the water left behind, giving us confidence in that conclusion."

Dr. James Garvin, lead scientist for Mars and lunar exploration at NASA Headquarters, Washington, said, "NASA launched the Mars Exploration Rover mission specifically to check whether at least one part of Mars ever had a persistently wet environment that could possibly have been hospitable to life. Today we have strong evidence for an exciting answer: Yes."

Opportunity has more work ahead. It will try to determine whether, besides being exposed to water after they formed, the rocks may have originally been laid down by minerals precipitating out of solution at the bottom of a salty lake or sea.

The first views Opportunity sent of its landing site in Mars' Meridiani Planum region five weeks ago delighted researchers at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif., because of the good fortune to have the spacecraft arrive next to an exposed slice of bedrock on the inner slope of a small crater.

The robotic field geologist has spent most of the past three weeks surveying the whole outcrop, and then turning back for close-up inspection of selected portions. The rover found a very high concentration of sulfur in the outcrop with its alpha particle X-ray spectrometer, which identifies chemical elements in a sample.

"The chemical form of this sulfur appears to be in magnesium, iron or other sulfate salts," said Dr. Benton Clark of Lockheed Martin Space Systems, Denver. "Elements that can form chloride or even bromide salts have also been detected."

At the same location, the rover's Mössbauer spectrometer, which identifies iron-bearing minerals, detected a hydrated iron sulfate mineral called jarosite. Germany provided both the alpha particle X-ray spectrometer and the Mössbauer spectrometer. Opportunity's miniature thermal emission spectrometer has also provided evidence for sulfates.

On Earth, rocks with as much salt as this Mars rock either have formed in water or, after formation, have been highly altered by long exposures to water. Jarosite may point to the rock's wet history having been in an acidic lake or an acidic hot springs environment.

The water evidence from the rocks' physical appearance comes in at least three categories, said Dr. John Grotzinger, sedimentary geologist from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge: indentations called "vugs," spherules and crossbedding.

Pictures from the rover's panoramic camera and microscopic imager reveal the target rock, dubbed "El Capitan," is thoroughly pocked with indentations about a centimeter (0.4 inch) long and one-fourth or less that wide, with apparently random orientations. This distinctive texture is familiar to geologists as the sites where crystals of salt minerals form within rocks that sit in briny water. When the crystals later disappear, either by erosion or by dissolving in less-salty water, the voids left behind are called vugs, and in this case they conform to the geometry of possible former evaporite minerals.

Round particles the size of BBs are embedded in the outcrop. From shape alone, these spherules might be formed from volcanic eruptions, from lofting of molten droplets by a meteor impact, or from accumulation of minerals coming out of solution inside a porous, water-soaked rock. Opportunity's observations that the spherules are not concentrated at particular layers in the outcrop weigh against a volcanic or impact origin, but do not completely rule out those origins.

Layers in the rock that lie at an angle to the main layers, a pattern called crossbedding, can result from the action of wind or water. Preliminary views by Opportunity hint the crossbedding bears hallmarks of water action, such as the small scale of the crossbedding and possible concave patterns formed by sinuous crestlines of underwater ridges.

The images obtained to date are not adequate for a definitive answer. So scientists plan to maneuver Opportunity closer to the features for a better look. "We have tantalizing clues, and we're planning to evaluate this possibility in the near future," Grotzinger said.

JPL, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, manages the Mars Exploration Rover project for NASA's Office of Space Science, Washington.

For information about NASA and the Mars mission on the Internet, visit http://www.nasa.gov.

Images and additional information about the project are also available at http://marsrovers.jpl.nasa.gov and http://athena.cornell.edu.

Guy Webster (818) 354-5011

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California

Donald Savage (202) 358-1547

NASA Headquarters, Washington

NEWS RELEASE: 2004-074